Have you ever checked out the website earth911.com? I’ve checked it out plenty when it comes to finding recycling avenues for anything imaginable…but I never thought to see if they had any material on composting. It turns out that they do, and I’ve been asked a lot about starting a compost pile in the winter. While composting isn’t easy in the wintertime, it is doable. Let’s see what earth911 has to say about it in the article below…

Just as you started to get into a solid groove with your compost pile this past summer and fall, churning over plentiful amounts of that beautiful garden gold, BAM! Winter hits.

But don’t throw in the shovel just because a white blanket of snow or a hardened sheet of ice now sits atop your compost pile. To help you get through the winter and ready to go once spring returns, learn some of the ins-and-outs of winter composting.

Listen to the experts

According to the University of Illinois Extension, “Composting [is] a biological process that decomposes organic material under aerobic ([meaning] oxygen [is] required) conditions. […] Composting speeds up the natural process of decomposition, providing optimum conditions so that organic matter can break down more quickly.”

In other words, a compost pile is an intentional strategy to speed up the decomposition process that nature, left alone, would take years to accomplish. To decompose at the rapid pace described above, the U of I Extension asserts that a main goal when composting is to promote the existence and propagation of aerobic bacteria.

Luckily for you, these compost dwellers are not picky eaters. And when they eat, they can turn up the heat – literally. According to the U of I Extension, aerobic bacteria heat up a compost pile when they eat, through the chemical process called oxidation. They especially love the carbon-rich (often called brown) materials, which give them energy. Another essential ingredient for your pile, nitrogen-rich (often called green) materials, help the bacteria grow big and strong and reproduce.

But why all the talk about the nutrient needs and chemical processes of bacteria? These factors can help us better understand why in the winter, at least if you live in a cold spot, composting is a different beast than it was in those warmer months.

The winter slow down

It happens to humans, so why can’t it happen to bacteria? The gray dreariness that often makes us want to go into hibernation mode (if only work, life, etc. would let us) also affects aerobic bacteria, in a manner of speaking.

The University of Illinois Extension says “warmer outside temperatures in late spring, summer and early fall stimulate bacteria and speed up decomposition. Low winter temperatures will slow or temporarily stop the composting process.” But fear not: “As air temperatures warm up in the spring, microbial activity will resume.”

Because ambient air temperature affects the speed of decomposition, when the temps cool down, so too does the aforementioned oxidation process. Instead of the voracious eaters they were in the summer and early fall, aerobic bacteria revert to a calmer state.

Yet even when the temperature drops, microbes responsible for the breakdown of organic matter can remain active in the compost pile, according the Texas AgriLife Extension Service. The center of the pile can be warm and actively composting because of heat generated by bacteria, but the outer layers of your pile are at the mercy of the daily highs and lows.

Furthermore, a compost pile needs the right amount of air and water (in addition to carbon and nitrogen) to be successful. So, when that winter snow and spring rain keeps on coming, your pile can get drenched. While water in the summer may be a necessary amendment, too much winter water will force air out of pore spaces in your compost pile, suffocating our dear aerobic bacteria friends.

Strategies for success, despite the cold

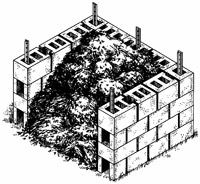

Here, a cinder block structure surrounds a compost heap. A block structure is one way to maintain internal pile heat longer into the winter. Photo: University of Illinois Extension

Here, a cinder block structure surrounds a compost heap. A block structure is one way to maintain internal pile heat longer into the winter. Photo: University of Illinois Extension

There are measures you can take to protect your pile from the elements and keep it viable further into the winter months. Here are some suggestions:

1. Build a roof. You have one over your head, why can’t your pile? Control external environmental factors by protecting your compost pile from unwanted precipitation.

2. Block it in. You may have noticed that the car in the garage or in the carport tends to be less frost-ridden in the morning than the car parked in the street. Without the protection of the house or other built structure, the car in the street is exposed to a bigger swing in nighttime temperatures.

Same principle applies to your compost pile. If you compost with heaps, build a protective barrier around your pile. If you already compost in some type of holding unit, you (and your compost pile) are covered.

3. Lay down a tarp. Putting a tarp over your compost pile not only whisks away unwanted precipitation, but it also helps contain the internal heat from the pile where you want it – in the pile.

4. Make a bigger heap. Extend the longevity of your pile by prepping early. According to the University of Illinois Extension, “During [the] fall months, making a good sized heap will help the composting process work longer into the winter season.”

Holding units are an alternative to heap piles, and can help protect the compost from winter elements that tend to slow the decomposition process. Photo: University of Illinois Extension.

Holding units are an alternative to heap piles, and can help protect the compost from winter elements that tend to slow the decomposition process. Photo: University of Illinois Extension.

Because volume is a factor in retaining compost pile heat, the U of I Extension suggests that for those in the Midwest, piles should be at least one cubic yard. The Midwest gets pretty cold, so it’s likely safe to say that this measurement suggestion can apply elsewhere in the U.S.

5. Shred it. According to the Texas AgriLife Extension Service, “Shredding the material in the pile to particles less than two inches in size will allow [the pile] to heat more uniformly and will insulate it from outside temperature extremes.”

6. Dig a hole and bury it. Another tip from the Texas AgriLife Extension Service suggests digging a trench in the garden or flowerbed and adding organic wastes like kitchen scraps (hold the meat, grease or animal fat, please!) little by little, making sure to bury the waste after each addition.

Similarly, “compost-holing,” or digging a one-foot deep hole anywhere in the yard and covering with a board or bricks until full of organic wastes, is another strategy to beat the winter cold and keep on composting.

Right method for the right place

In the end, it is always important to consider what type of system works best for you. The area available for composting, seasonal climate, along with the time commitment you are willing to give to your pile, all impact the type of composting system that would work best. Always do your research when looking to start, continue, or try a new type of composting system.

I had fun worm composting, until I over feed and got fgunus gnats. I have plans on rebuilding a differnt worm bin, but with our AZ summer heat plus/cold winter, I have to keep the worm bin inside. I’ve used up all my “let me just try this and see if I can get rid of the gnats” chances you know what I mean I’ve had some good luck with composting under a little shade. I was turing it each week religiously which might not be the ideal task with so many other things to do.