Although I’m super late to this article, I had to repost it due to its importance and the fact that I haven’t seen any updates on it since this was posted.

Hopefully they can get it passed, although I think bans should be as stringent as Vermont’s, which bans all food waste residentially and commercially by 2020.

Original source found at: http://patch.com/new-jersey/middletown-nj/happy-holidays-s-2494-would-ban-commercial-food-waste-nj-landfills

Just in time for the holidays, Senator Raymond Lesniak introduced a bill on October 14th that would ban large commercial institutions from disposing their food waste in landfills and incinerators in NJ.

That would be like Thanksgiving for those who struggle with hunger, because it would make donating food to food banks a practical business decision.

It would be like Christmas for everyone, because it would:

- Reduce landfill emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas that has 21 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide

- Prolong the life of landfills. Food waste makes up 20-25% of the garbage going to NJ landfills. That makes it the next logical choice to add to the list of stuff that needs to be recycled statewide ( page 88). When their landfill is full, local taxpayers are going to be on the hook for siting a new one, building an incinerator – or railing their trash to another state.

- Make use of the irrigation water now being wasted on food that becomes landfill leachate every year. According to the World Health Organization, the US wastes over 13 trillon gallons of water every year on food sources that never become food.

The Bill

S-2494would require businesses and institutions in NJ generating 104 tons a year of food waste to send it to a composting or recycling facility rather than a landfill.

A food waste recycling facility uses biological processes like anaerobic digestion, or heat in an in-vessel food waste dehydrator to process food and soiled or unrecyclable paper like napkins and paper towels into fertilizer, electricity or natural gas.

The bill would regulate only the largest generators – universities, not high schools – and only businesses and institutions, not residents.

But there aren’t any large recycling facilities in NJ yet. There is one state-licensed food waste recycler in NJ, in Sussex County, that composts about 10,000 tons of food waste a year.

So during the first year, only the large commercial generators located within 25 miles of a facility authorized by the NJDEP to recycle food waste would have to comply. After a year, they all would – regardless of distance.

There are already several food waste recycling facilities in the pipeline in NJ. A Food-Waste-to-Energy facility on a brownfieldin Gloucester City, Camden County, would treat 200 to 400 tons per day in 2015. Waste Management, Inc. has an application before the NJDEPto build a facility on an existing solid waste transfer station in Elizabeth that would grind food waste for composting or further treatment in a sludge digester at a wastewater plant, according to Sondermeyer. Trenton Biogas is proposing to convert an unused sludge plant on Duck Island in the Delaware River to turn up to 100,000 tons a year of food waste into fuel and fertilizer.

S-2494 is very close to what the Association of New Jersey Recyclers had proposed this spring that was modeled on the Food Residuals Recycling law in Rhode Island.

The White Paper

As reported October 10th on the EnviroPoliticsblog, Gary Sondermeyer of ANJRthinks that even a moderate approach to regulating food waste would help NJ reach its goal of recycling 50% of its solid waste. That’s because food waste is as much as 25% of what gets thrown away as garbage in NJ, according to Sondermeyer.

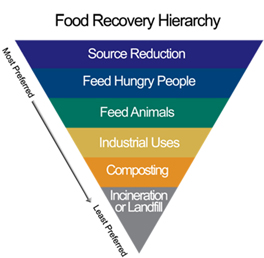

In March, ANJR proposedthat only institutions that produce 104 tons or more a year of food waste (an average of 2 or more tons a week) be required to recycle, repurpose, or donate, rather than dispose. But only when a large generator is within 35 miles of a recycling facility, and only when the cost of recycling is less than disposal. Other states that have been recycling food waste report savings of 20-25% over disposal costs, according to Sondermeyer.

Four States With Bans

In 2011, Connecticutbecame the first state to ban commercial food waste from landfills. Generators of 2 tons or more food waste per week were required to recycle if located within 20 miles of a recycling facility. In 2013 they expanded the ban to facilities generating a ton a week, beginning in 2020.

In 2012, Vermontbanned food waste from commercial generators within 20 miles of a recycling facility that produced 2 tons or more food waste per week. Allfood waste, residential as well as commercial, will be banned by 2020.

The Massachusettsban on commercial food waste took effect October 1, 2014. Facilities producing 1 ton or more a week are required to donate, repurpose, compost, or convert their food waste to animal feed. There are no distance restrictions because they already have s o many recycling facilities.

The Rhode Island ban – the one NJ’s is modeled after – takes effect Jan. 1, 2016 for facilities generating 104 tons or more food waste a year within 15 miles of a recycling facility. However, these institutions can send their food waste to the landfill if it’s cheaper than recycling, and K-12 public schools are exempt.

What About Eating Out-of-Date Food?

The Foodbank of Monmouth and Ocean Counties trains their staff in food safety. Their warehouse is certified in the federally-standardized process widely used for the prevention of food hazards ( Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points).

But what about expiration dates on food? Whether it is shelf-stablefood that doesn’t need to be refrigerated, or Potentially Hazardous Food that has been kept at the appropriate temperature, most dates are about peak quality, not food safety. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, “U.S. consumers and businesses needlessly trash billions of pounds of food every year as a result of America’s dizzying array of food expiration date labeling practices, which need to be standardized and clarified.”

The NJ Department of Health only requires expiration dates for bottled water and fluid milk products, including creams and yogurts ( #5), for controlling the growth of bacteria that cause disease. According to the USDA, infant formula under FDA inspection must have a “use-by” date on the label so that formula doesn’t clog a nipple. The other dates are about spoilage, not disease – even the sell-by dates on meat are for rotating stock, not for safety.

Meanwhile, Here’s Who Won’t Be Getting Fossil Fuel in Their Stockings

Kean University has been composting its on-campus food waste since January of 2010, the same year the NJDEP set aside $200,000 in grants for colleges and universities to start pilot programs for recycling food waste. Their rotary drum composter in the Food Scraps Composting Laboratory – their Green Machine – can process 250,000 pounds of food scraps in less than a year.

The municipality of Princeton has been picking up organic waste at the curb once a week since 2011 for residents who want it, for $65 a year. This includes food, soiled paper products, and most yard waste. Here’s what they will collect: If it grows, IT GOES.

The Hackensack University Medical Center has been sending its food waste, including biodegradable cups and plates, to a digester in a corner of its kitchen since 2013. It turns 400 pounds of food waste into about 100 pounds of water in four hours, diverting 250,000 pounds food waste from the landfill in its first year.

An Environmental Regulation that Fights Hunger

Emergency food. Food-insecure.

There was a story Friday in the Patch about a family in Middletown that is filling backpacks with weekend-food for families in their school system that are still affected by Superstorm Sandy. In their recent press release for Hunger Action Month, the Monmouth County Board of Chosen Freeholders reported: “The sad fact is more than 80,000 people in Monmouth County face hunger every day, many of whom are formerly working, middle class families who lost their jobs or are underemployed.”

Poverty and pollution. S-2494 could make donating food to food banks cost-effective. It’s one way environmental goals can cross over to directly fight hunger. The Senate Environment and Energy Committee meets Monday, October 27 to discuss it.